In my last two posts, I shared two hard truths about taking responsibility: The World Owes You Nothing and The Cavalry Ain’t Coming. I emphasized that there is no substitute for the hard, grinding work of creating change, and innovators should not look to the horizon for a miraculous rescue.

Today’s hard truth is almost an inversion of the last two: the world does not rest on your shoulders.

I squirm, writing that.

Of all these hard truths, that one might be the hardest for me. I cannot say I have fully internalized it. I am preaching to myself as much as to you.

My expectation of disaster

I was once Aircraft Commander for a C-17 mission supporting a Secretary of Defense visit to three South American countries. We were to shadow his business jet from airport to airport in case it had maintenance issues, and personally carry him and his entourage to an austere airfield the business jet could not reach. This was what military officers call a “no-fail” mission. The logistics were complex. We spent weeks coordinating details like passports, visas, landing fees, instrument approaches and departure procedures, and fuel services.

The individual who processed passports and visa requests at our base was one of the most difficult government employees I have ever met. He made so many mission-impacting mistakes and lost so much paperwork that we started a spreadsheet to track incidents. He was always acerbic and always denied responsibility. He could not be fired and we could not work around him.

Days before this no-fail mission–during my daily, paranoid checkups on his work–I learned he had mailed the entire crew’s passports to the wrong office, which meant we would have none of the visas needed to enter the three countries where SECDEF was traveling. I spent the next three days on the phone with embassies and agencies across Washington D.C. We worked out a convoluted plan that involved a forward-leaning bureaucrat (the hero we all need!) driving all over Washington D.C. to obtain visas, then hand-carrying passports to a base where we would be making a fuel stop en route to South America. We pulled it off–barely. Had it not been for our paranoid attention to detail and concerted effort to create a solution, we would have fumbled one of our most important missions of the year.

This is an especially egregious example, but I have had experiences like these over and over in my career. So many times when I have trusted the system to work, it let me down. Support agencies have lost my paperwork, forgotten to write my annual performance reports, nearly ruined my promotion boards, and screwed up geographic moves for me and my family.

The problems compounded when I started leading aircrews and teams. Every C-17 pilot can relate; the flight crew is the last line of defense in an incredibly complex orchestration of agencies that have a role in mission success. Aircraft Commanders spend a disproportionate amount of their energy monitoring this symphony and then swooping in to fix impending disasters: the passengers are late, the wrong cargo shows up to the jet, diplomatic clearances aren’t properly coordinated, headquarters planned your flight to a closed airfield. You quickly learn to expect disaster. You learn to trust no one but yourself and (usually) your crew.

This expectation occurs in a context where the vast Air Force mission enterprise is doing exactly what it was trained and built to do.

When you lead change, things gets even harder.

Now you are stretching the organization out of its familiar patterns and rituals. You are introducing new workflows and tools, trying new tasks and behaviors, attempting to use support functions in novel ways. Nobody is fully trained for this. Everyone is learning together–including you. Oversights, mistakes, and inadequate work are endemic. You are juggling a thousand details, and because you as the change-maker are carrying so much risk, one dropped ball could sink your entire effort.

Over the years, these experiences have left an indelible imprint on me.

There are very few people I trust completely.

Everything rests on my shoulders, I think.

And that belief is dangerous.

Life in the paradox

At first, this might seem to contradict my last two posts. Haven’t I been writing that leading innovation requires taking ultimate responsibility?

Yes. But.

It would be handy if a single set of principles could offer sure guidance through all the messy ambiguity of life. However, real life generally embodies paradoxes: two apparently irrreconcilable propositions that are both absolutely true. You must work hard but not overvalue work. You must strive for success but anticipate and make your peace with failure. You must be generous in relationships but also set boundaries. You must give your children sound instruction but also let them learn from their mistakes. A well-lived life entails constantly navigating these paradoxical tensions.

This is no different.

When you lead innovation, you must take ultimate responsibility for the outcomes you wish to achieve. You must learn to rely on your own resources, creativity, ingenuity, and hard work. You should not expect others to carry your burdens or swoop in to rescue you.

At the same time, however, you cannot carry this burden alone.

If you try, you will not last long.

Resolving the paradox

Creating change in entrenched systems is hard. Incredibly hard.

Hundreds or even thousands of people have labored for years to make the system what it is. The system is the emergent outcome of financial investments, sales histories, defeats, victories, legal battles, and untold expenditures of time and energy. Previous generations built this cathedral brick by brick, with all its majesty and all its imperfections. Intrapreneurs just as passionate as you put their blood, sweat, and tears into shaping, sanding, and polishing it to perfection.

And here you are. One person. Standing in defiance.

There is nobility in that. That is how any great change or creative work begins–in moments when, as Steinbeck wrote, “a kind of glory lights up the mind of a man.” An inspired leader has a fleeting glimpse of a different future, with no idea how to make it real in the face of such overwhelming odds, but takes the first step in faith anyway.

Now you are in the arena, and your adversary is so much stronger. The combined might of that vast system will be brought to bear on you.

This will not be a quick or easy battle. You will quickly realize that you must settle in for the long haul, that you need allies, that this one battle will likely unfold into a campaign lasting years–perhaps even generations.

You will need to fight tirelessly, but you will also need to manage your energy and your health. You cannot possibly comprehend all the million details that will be need to be resolved, nor the alignment of forces that will need to occur to make lasting change. You will also discover that althrough your basic intuitions might be right, your grasp of the details is incomplete or even profoundly wrong. Your ideas must evolve, often through rigorous testing and profound challenge.

To lead change, then, you need other people. You need a team. You need allies. You need to synchronize your efforts with many others who are fighting similar battles in other places. You might even need enemies.

You also need to recognize that by stepping forward in opposition, you are opening yourself to forces beyond your control. Think about Martin Luther nailing 95 theses to a church door, Rosa Parks refusing to give up a bus seat, or Billy Mitchell using an airplane to sink a Navy ship. The contexts were extremely different, but in each case, an individual picked a fight that would reverberate through the halls of power and ripple across vast swaths of society. These acts challenged institutions, cultures, ideologies, and norms. The reformers had no way of knowing precisely how incumbent forces would respond, but one thing was certain: the response would be big, and it would be beyond their ability to control.

Reform often requires surrender, then–not giving up, but yielding ultimate control to forces and processes far bigger than ourselves.

If we persist in believing that this burden falls entirely on our shoulders, we place impossible expectations on ourselves. We will be broken–either in one fatal blow, or through the accumulated weight of unmanageable challenges.

The hard challenge

Living with this tension is hard–and one of my biggest personal challenges.

The paradox plays out every day. In my various innovation projects, I have been the chief “vision owner” and have spent thousands of hours mastering complex implementation details. I believe my personal ownership of wide-ranging details is what makes me effective and allowed my previous initiatives to make it as far as they did.

At the same time, I place impossible expectations on myself. My time leading Uplift Aeronautics shattered my mental health, which set me on a long journey of soul-searching and healing. I approached Rogue Squadron with more wisdom and balance, and we built a stellar team and coalition, but I still repeatedly found myself stumbling under the burden. Especially as our team grew, I struggled every day with where to maintain personal control and where to surrender that control to forces outside myself. There was rarely a clear answer; it was all tradeoffs. I have entrusted control to others and watched disaster ensue; I have also entrusted control and watched colleagues achieve feats I never could have imagined.

Navigating the paradox is a deeply personal journey that every innovator must make. You are ultimately responsible, and yet the weight is not on your shoulders alone. It is your determination and hard work that will create change, but forces beyond your control are in play. You must be detail-minded and self-reliant but also trust and lean on a broader community.

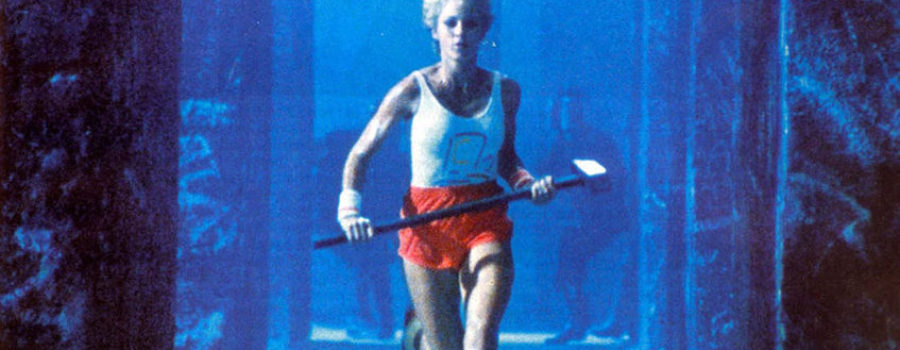

Image taken from Apple’s classic 1984 ad–which, incidentally, was recently subject to a brilliant recreation by Epic Games as part of its legal battle with Apple.