Over the last ten years, government has at least theoretically embraced the idea of “innovation.” New innovation organizations are popping up like mushrooms. Poor private sector; every time they think they have figured out how to work with government, some new organization appears on the scene to shake things up.

This widespread culture shift toward innovation is generally a good thing. However, time and again, I have seen innovation organizations appear that do not have a clear purpose, business model, or theory of innovation. Despite good intentions and strong support, many of these organizations struggle to create enduring value. Some hold a plethora of glitzy events without ever moving money, developing prototypes, or running experiments. Others write proposals and build prototypes but never scale these early concepts into wide-scale adoption. So much innovation activity dissipates like water into sand, while government rumbles on as it always has. I suspect similar dynamics occur in many large companies attempting to become more innovative.

Over many years pondering these challenges, I have developed some basic models of common innovation approaches. These models can:

- Help you intentionally develop a theory and strategy of innovation for your organization

- Suggest reasons your strategy might not be working

- Help you understand where your organization fits in a broader landscape

The models are simple by design and hardly comprehensive, but they offer a basic scaffolding for deeper thought about your own unique situation. No one model is right or wrong.

The Core: Innovation Pipelines

Innovation is a process of discovering and implementing value-adding changes for customers. These might include physical technologies–like new hardware or software–or social technologies like strategies, processes, workflows, or ways of organizing.

Customers could refer to literal paying customers of a product, but they could also be stakeholders within an organization or community who stand to benefit. In my defense work, my customers were usually warfighters who needed every tactical advantage on the battlefield.

Systematic innovation efforts involve an innovation pipeline. Above is just one example I plucked off of Google, largely because of its simplicity. You can divide out the stages many different ways, but a pipeline generally includes the following:

- Idea generation: Gather as many ideas as possible, good or bad; we deliberately keep a wide aperture.

- Prioritization and filtering: Prioritize ideas in accordance with our organizational needs, resources, and values. Identify the ideas worth pursuing.

- Refinement: Explore both problems and solutions, widening the aperture again to consider both from every possible angle. Turn the idea into a viable concept, which represents an educated hypothesis about a potentially valuable innovation.

- Experimentation: Commit progressively more resources to experimentation, learning, and iteration. Test and refine the hypothesis to see if this idea is worth scaling.

- Scaling: Scale the most promising ideas into wide-scale execution. This might mean releasing a new product, changing a policy, etc.

Software introduces some modifications, since you can take early ideas into production immediately and then iterate in place, but you get the general idea; if your goal is actually implementing change at scale, then you need a start-to-finish pipeline.

The goal

The ideal innovation pipeline would look something like this:

Assuming your organization is in a competition with adaptive adversaries, you need to act quickly. Whatever your pipeline looks like it should run fast. You need a faster OODA loop than your opponents, which includes observing your environment, educating your judgment, making decisions, and then acting swiftly and decisively.

You want to identify and implement value-adding changes for your customers with the greatest speed and efficiency possible.

Model 1: The Status Quo

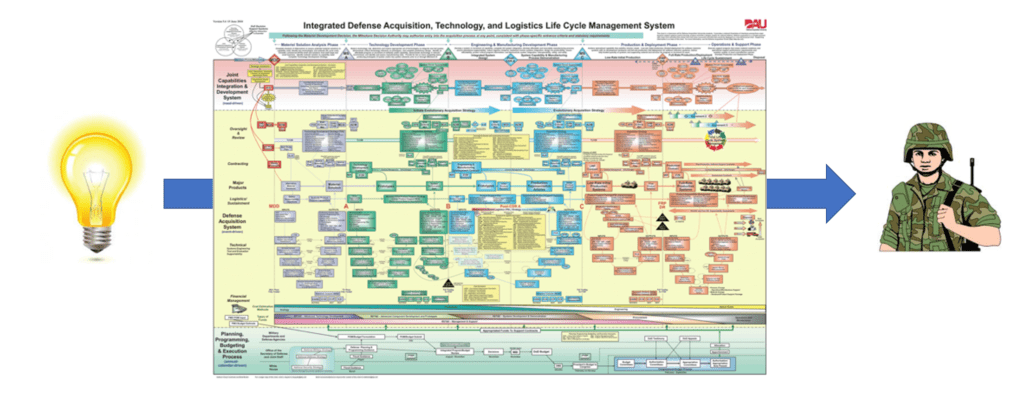

If you are in a large organization like the Department of Defense, your innovation pipeline looks more like this:

The chart in the middle is an actual diagram of the DoD’s acquisition process, which I chose mainly because it is so easy to pick on. The details aren’t important. This box, whatever it contains, represents all the convoluted bureaucracy that stands between a promising idea and scaled implementation. This is how we get to $10,000 toilet seat covers and $800,000 ammo rounds that are too expensive to fire.

Innovation does actually occur in this model. In fact, it occurs all the time.

That box includes a vast network of research labs, prototyping initiatives, and means of production. It includes systematic processes for every step of the innovation pipeline to include soliciting ideas, developing requirements, assessing feasibility, conducting experiments, doing limited-run production, testing, evaluating, and incorporating feedback. The system has delivered F-22s, aircraft carriers, and nuclear submarines. All those little boxes on the chart exist for a reason: in theory (!!!), they illuminate and/or reduce risk.

Every organization has its own version of this chart, which expresses how value-adding changes are realized and executed.

Before you found a new innovation organization, you need to know why this incumbent innovation process is not meeting your needs.

Many defense innovators would probably struggle with that question.

I will save my full answers for another day. For now, it’s enough to say that this pipeline works very well for certain kinds of problems but very poorly for others. It is intolerably slow when dealing with fast-evolving technologies like software, computation, or machine learning.

The impetus for more speed and agility largely drives government’s search for for alternative innovation models.

Model 2: The Idea Factory

This model rests on a hypothesis about what is wrong with the current innovation pipeline: senior management need help finding the right ideas.

When I assisted with founding the Defense Entrepreneurs Forum, this was our basic belief. We knew our senior leaders were sharp, dedicated, and talented professionals. We also knew they were swamped with hard problems and did not necessarily have the time or energy to solve all those problems themselves.

We believed that an organization of dedicated young military professionals could apply their collective brainpower to some of these problems and help generate solutions. The first DEF conference included two-day long “ideation” sessions, in which teams went to work on a curated set of problems. This culminated in pitches to a panel of general officers and investors.

With years of hindsight, I believe we misdiagnosed the problem. Our innovation model looked something like this:

Can you see the problem? Our model mostly addressed the earliest stage of the pipeline: injecting the right ideas into the funnel. While it’s true that an outsider can generate a truly novel idea, this stage is rarely where innovation gets jammed up. Ideas are cheap; the hard part is the other 99%, which is the execution that follows. Several of our presentations on the last day of DEF were cringeworthy, because in two days of ideation, teams simply couldn’t delve into the practical details necessary to walk an idea down the pipeline into execution. The most successful pitches came from innovators who had been working on a pet idea for years.

There is nothing wrong with brainstorming ideas, but these ideas will most likely be dead on arrival unless the innovation pipeline includes onramps that can get promising ideas to the next stage. Here are some ways to improve on the model:

- Connect promising innovators with senior leader champions. The hard part is identifying the right senior leader up front. Placing a senior leader or two on a judging panel is unlikely to bear fruit, because the odds that a particular idea falls within that leader’s scope is minimal. Ideas need the right champion to move forward.

- Award prize money. The intent here is to give innovators resources to carry their idea forward. Cash prizes give innovators the most agility, but by themselves, they provide little to no connective tissue with the rest of the innovation pipeline; the idea will only make it a little further before it dies.

- Protect innovators to keep them with their projects. On a few occasions, I have seen general officers reach down to hand-select an innovator to keep him or her with a project; this is every innovator’s dream, but it is ad hoc and not scalable. The fact that GOs must reach down from on high to protect an innovator is not a solution; it is evidence of systematic brokenness.

- Have established processes to connect promising innovators with organizational resources. This is the best solution, but the hardest for an entrenched bureaucracy like DoD to implement. Ideally, organizations would have built-in infrastructure to advance good ideas (and the innovators standing behind them) to the next stage of the pipeline. That would include budgeted funds, labs, tools, access to structured venues to meet with senior leaders, and–most importantly–talent. The best example I have seen of DoD building onramps was MGMWERX giving pitch competition winners access to Air Force-funded Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) funds in order to put a private sector company on contract.

Despite the shortcomings, this model can be an inexpensive way to cast a wide net, solicit ideas, and give unconventional innovators a voice. It is often the best that grassroots innovators can do.

Model 3: The Brain Trust

This model usually seeks to improve on Model 2. It begins with the recognition that grassroots innovators need senior leader champions to get very far. For that reason, a senior leader who wants innovation might create a “brain trust” of savvy employees who report directly to him or her. In the chart below, all this brainpower is nestled within that leader’s cell on the org chart.

This model improves on Model 2 by committing organizational resources to innovation. In theory, these innovators are given adequate top cover to focus on driving progress. Leading innovation is no longer a volunteer role slapped on top of their day jobs, but the thing they are paid to do day in and day out. The sustained commitment to innovation gives these individuals opportunities to actually tackle execution, and to do so with the boss’s support. The Chief of Naval Operations’ Rapid Innovation Cell (CRIC) comes to mind as a good example; the CNO was able to pull highly qualified talent from the Navy, including key members of DEF.

However, this model also has several challenges. First, for all the intellectual firepower these individuals have, they still comprise just one cell on the org chart. Their ability to work across the entire pipeline might be limited. Brain trusts can be very good at setting experiments or prototypes into motion, but DoD is absolutely terrible at crossing the valley of death between prototypes and production. Second, the survivability of the brain trust is highly dependent on the specific boss; the odds of getting two highly supportive, hard-charging bosses in a row are low. Third, a pool of brilliant employees with tremendous initiative will not go unnoticed, especially when they work in a higher headquarters; the temptation to poach these individuals for various initiatives and projects is high. Innovators may be torn in different directions and may not have adequate white space to focus on core innovation efforts. Finally, it is a key tenet of the literature on innovation in large organizations that innovative teams often need to be distanced from the core enterprise; it is the only way to avoid an incentive system overwhelmingly skewed against experimentation. Brain trusts that work directly for a mainstream headquarters may not be adequately insulated, and may find themselves outmaneuvered at every turn by entrenched interests.

Model 4: The Dedicated Innovation Organization

This model takes organizational resourcing to another level. Instead of relying on volunteers or placing a few key individuals under the protection of a supportive leader, this model involves creating specialized organizations to execute innovation. These organizations receive mandates, budgets, and other resources to own as much of the innovation pipeline as possible.

This model arguably encompasses much of DoD’s new innovation ecosystem. These organizations attract individuals who are passionate about innovation and who are eager to break out of old ways of doing business. They have enormous potential, but are also the most likely to struggle with a lack of clarity about their purpose. The best example I can give is my own DIUx; it struggled during its first year, which led Secretary of Defense Ash Carter to replace the leadership and reboot the entire organization. DIUx (later renamed DIU) later found a better operating model, but that took time. More on that in a moment.

As these shiny new innovation organizations seek to go “innovate”, they tend to land on similar activities, like industry days, collider events, design thinking sessions, ideation days, problem curation, road shows, tech scouting, hackathons, and pitch competitions. These activities can be valuable in their own right. They are fun. They make for great publicity. They feel like innovation.

The problem is that they are nearly all early-stage activities in the innovation pipeline. They are largely aimed at scooping up ideas, assessing feasibility, demonstrating technology, or–for the most mature organizations–advancing a prototype.

This is all good, but it brings a few problems. First, these organizations face deep structural challenges in crossing the valley of death between prototyping and production. Most ideas will die before they are fielded. Second, DoD’s vast number of organizations doing early-stage scouting can create real problems for industry. On the one hand, it is good that private companies have an unprecedented number of opportunities to do business with the government. On the other hand, a company executive could spend every week of the year going to tech demonstration events that never result in contracts being awarded. That gets old very, very fast.

Dedicated innovation organizations need to realize from the outset that crossing the valley of death will be their biggest challenge. Yes, they can have a lot of fun before they fall off the cliff. But if their goal is to create value-adding change for customers, they must solve transition. That means going beyond fun ideation sessions. It means doing the nasty, hard, thankless work of cleaning out the plumbing on the right side of the chart.

Model 5: VFR Direct

One way of dealing with the system is navigating around the system entirely. I call this VFR Direct, the aviation term for navigating straight to a location using your own eyeballs, without relying on instruments or air traffic control.

VFR Direct is where I have spent most of my time in my career. In this model, innovation teams essentially bypass the bureaucracy and use every tactic, technique, and hack at their disposal to get a capability directly to the end user. In my case, as a software developer, this has often meant writing and distributing my own software. As a solo developer I wrote useful programs, shared them with my peers, and created my own website to distribute them. Word spread, and my capabilities found their way into widespread use.

Later, we built Rogue Squadron on this model. Our team benefited from a central funding source, high trust from DoD leadership, and little day-to-day interference, which allowed us–as we said–“to skate where the puck was going.” Our expert team was so attuned to new developments in the drone market that we could leverage new capabilities within weeks or even days of their release, or even plan new capabilities based on expectations of where the drone sector was going. We built relationships directly with warfighter units, built capabilities at their request, and delivered capability the instant it was ready. We built our own web infrastructure for managing and deploying software updates, so we could push code changes in moments to our users across the globe. We crossed the valley of death–for a time–by playing by an entirely different set of rules.

I love this model and always will. This is where I personally thrive, and I believe government needs more teams like this given the accelerating pace of technological change in today’s world. The philosophy of Mission Command is premised on setting intent but allowing for decentralized execution by trusted units. In today’s world, that should apply just as much to capability developers as to infantry. But I digress…

This model does have obvious shortcomings. The bureaucracy theoretically exists to illuminate risk, whereas VFR Direct runs the risk of hiding it (although I believe this distinction is often false in practice–the subject for another article). This model can also obfuscate the ownership of risk because it is sometimes less clear who is signing off on risks.

Furthermore, it is the team’s ability to operate outside of the parent organization that allows it to move so quickly and with so much agility. The downside is that the team has little institutional support when needed. DoD is not structurally capable of providing sustained resources to teams that operate outside its close supervision. These teams must continually take calculated risks by operating outside of normal conventions. They run the risk of antagonizing the establishment and face serious sustainment challenges.

Teams operating on this model also have a complexity ceiling, because more complex projects require more engagement with broad stakeholder groups.

The sweet spot for VFR Direct innovation is probably fielding urgent, niche, time-sensitive capabilities while waiting for the establishment to catch up.

Model 6: Fast Track Innovation

The most mature innovation organizations take ownership of the entire innovation pipeline, from early-stage idea collection to long-run fielding and sustainment. This is very, very hard to do.

One approach is to build an innovation organization around legitimate fast-track authorities that allow for quickly maneuvering through the bureaucratic maze.

After its reboot, DIU focused its business model around Other Transactional Authorities–an acquisition authority originally created to help NASA move quickly in the Space Race. OTA contracts can be fast and lightweight, bypassing much of the red tape that constrains more traditional acquisition processes. This introduces risk in some areas but reduces risk in others–especially if, like me, you believe that speed is its own source of advantage and that moving slowly introduces tremendous, often unrecognized risks. DIU built its own process called the Commercial Solutions Opening, which packages OTAs in an easy package that the private sector can understand and work with.

AFWERX built its own fast-track model around Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, which allow government to put small businesses on contract and then progressively add resources as an idea proves its value. AFWERX’s innovation was not so much its use of the SBIR, but the sheer number of them it doled out. In one day in 2019, the Air Force awarded 51 proposals in 15 minutes or less. The SBIR initiative showed a new commitment to placing small bets, which is generally considered good practice when planning for uncertain futures.

This general approach strikes me as the most promising for accelerating government innovation, but it is not a panacea. I will explore this in future articles, but even fast track authorities are not usually enough to cross the valley of death. DoD has an ever-increasing number of contracting vehicles and funding mechanisms for prototyping, but at the end of the day, programs can only be implemented and sustained if they are programmed into the defense budget. That Byzantine process has a five-year lead time, and funding flows through the very program offices that these rapid innovation organizations are often trying to work around–and often compete with. This puts rapid innovation organizations in a difficult dilemma: if they have an antagonistic relationship with program offices, their experiments will never see the light of the day. However, if they coordinate with program offices from the beginning, they will have to make numerous compromises that will gradually funnel them into the same mindset and behaviors that they were originally founded to escape.

This Faustian bargain is the dirty secret at the heart of defense innovation: to scale beyond prototypes, you have to become just like the thing you sought to avoid. This is where reform efforts must be targeted; nothing will ever really change otherwise.

Model 7: The Coalition Model

For years, I only had the above six models in my repertoire. Over time, I gradually realized that I needed another. This capstone model encapsulates most of my day-to-day experience as an innovator.

The Coalition model acknowledges that there are wonderful people to be found everywhere in that vast, bleak Borg cube of defense acquisition, with its incomprehensible acronyms, endless arrays of office symbols, and soul-sucking processes.

We are all in this mess together, and getting any damned thing from one end of the pipeline to the other is a pick-up game that requires a coalition of hardened fighters.

There are brilliant inventors churning out ideas at the grassroots. There are savvy, insightful commanders trying to move chess pieces around the board to get the best ideas into execution. There are passionate staff officers working in headquarters who want to see change. There are brilliant people working in the program offices who hate the constraints they are under but will use the full envelope of their authority to do the right thing. There are dedicated and loyal civil servants deep within the notorious “frozen middle” who are absolutely essential to getting ideas resourced, approved, and into the field.

When you really delve into a specific problem or solution space, you quickly figure out who the power players are. You find each other on the sidelines of conferences. You meet at dive bars on business trips to plan strategy. You text each other during 75-person telecons, because at the end of the day, you know the five of you will be the ones actually driving change.

My most successful experiences with large-scale innovation came through these kinds of coalitions. A few examples:

- Rogue Squadron began when high-level officials in the Office of the Secretary of Defense saw our value, supplied us with resources, and then trusted us to do the right thing; they provided the rails within which we operated, ensuring we stayed compliant and approved.

- Later, we built an extraordinary partnership with a major Combatant Command headquarters. We built effective alliances with a rock star team of staff officers, civilians, and contractors at the headquarters, who shouldered the brunt of the “bureaucratic warfighting” and left Rogue Squadron free to keep developing and delivering capability at blistering speed.

- DoD recently announced five new trusted quadcopters built for the Army, which will soon be available to the entire government. This extraordinary program emerged from a novel partnership between a forward-leaning Army program office and DIU. The Army program office brought institutional support and requirements, while DIU brought its contracting authorities, private sector relationships, and domain expertise.

Conclusion

Any model is a simplification of a more complex reality. These models are no different. Undoubtedly there are many ways to divide up the complex landscape of innovation activities across an enterprise as vast as DoD, but these models make sense to me and emerged through years of practice and reflection.

If you are a leader of innovation, think about your own conceptual models. Consider where you might fit. Any conceptual framework will not fit reality perfectly, but it can at least give you a scaffolding to build on as you find your own way forward in your own unique context.