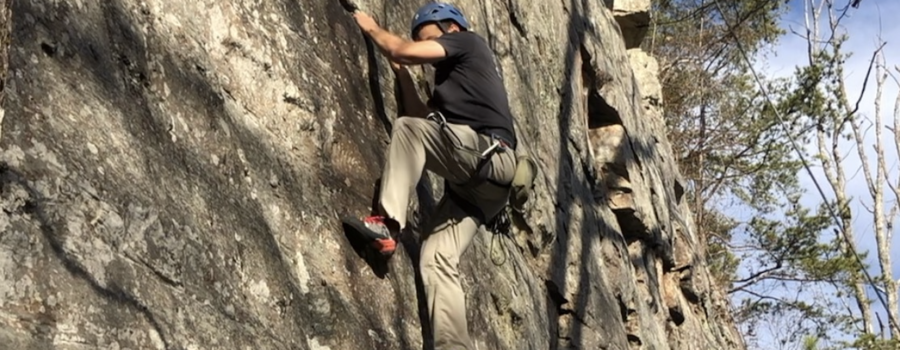

When I started seriously rock climbing, I used a safe and static climbing style. I always kept three points of contact, carefully reached for the next handhold or foothold, and gingerly shifted my weight to ensure my feet would hold. Only when I was certain would I commence my next move.

This worked—for a little while. It is a good way to climb the easiest routes at the gym. It gets you familiar with the basic movements of climbing, and helps you overcome your fear of heights without much risk of falling. However, once you move beyond beginner grades, that style of climbing no longer cuts it.

To get up most climbs, you have to make what climbers call committing moves. These are moves that you can’t safely test before making them; once you initiate them, they are irreversible. Often times, you need to put weight on tiny nubs that you can’t possibly believe will hold you. Other times you need to hoist your body up on a heel hook, which will give you a split second to grab the next handhold. Still other times you need to make dynamic moves that rely on momentum.

You either finish the move, or you don’t. If you don’t, you fall.

Committing moves can be terrifying. Even experienced climbers do not like to fall; falling is scary, and many fall situations involve at least some risk of injury. A skilled climber makes continual risk calculations as she moves over the rock. It is in committing moves where her mental game is honed and put to the test.

Committing moves in life

I love this concept of committing moves as a metaphor for entrepreneurship and life. It provides such a tangible and visceral image for the decision points we often face.

Many people never want to make committing moves; they fear irreversible decisions, particularly when they perceive risk. They fear marriage. They fear quitting their job or taking a loan to launch a small business. They hesitate to speak up with a contrary opinion, because once they do, there is no going back.

To live without making committing moves is to stay on the beginner walls. One can enjoy a safe and contented life that way, but growth opportunities are limited.

I am conservative with risk, but many of my biggest life gains came through committing moves. I married Wendy (although I had no doubt about that one). We had kids at a time when life seemed impossibly busy (I felt pretty good about that one too). On a couple occasions we bought houses instead of renting, which worked out well. I founded Uplift Aeronautics. Later, I founded Rogue Squadron and accepted a scary amount of funding to scale. My entrepreneurial experiences were hard and involved many falls, but were the most satisfying and enriching experiences in my professional life. I wrote pieces for publication. In most of these cases, I can thank friends and family for pushing me to take risks I was afraid of.

Running a business or organization is filled with committing moves, because you must often make irreversible resource commitments with long lead times before the results come in. Yes, you should make use of small bets and low-risk experiments whenever possible, but you often need to put all your chips in.

The psychology of commitment

There is an entire psychology around how we make committing moves. My favorite treatment comes from Arno Ilgner’s wonderful book The Rock Warrior’s Way, which is a great manual for life even if you do not climb. We can roughly divide the decision process into two parts: before we choose to commit, and after.

Before we commit, we need to observe ourselves. We must tame our own psychology; if we are riddled with negative self-talk like fear or doubt, we must identify and eliminate it, because it will do nothing to help us. We should approach a committing move relaxed and confident.

We must accept the situation as we find it, not waste precious energy wishing or pretending it were different. We must study the details closely, and focus our attention on every possible source of advantage. Our senses should be attuned to possibilities, not obstacles.

However, we must also understand the risks entailed. We should consider very carefully what happens if we successfully make the move, but also what happens if we fall. We do ourselves no favors if we lie to ourselves about the danger we face. Pretending away risks is a terrible strategy. We can use exercises like murder boards and pre-mortems to help illuminate the real risk.

Then comes the moment of decision: do we commit, or do we not?

Both are acceptable decisions. If a risk is not worth it, we can downclimb or get lowered. In life, we can back away from the venture or purchase or relationship. Nothing is lost. We have learned something about ourselves in the process, and will be better-equipped to face similar moves in the future.

But once we make the decision to commit, we must commit 100%. There is no longer any going back. You have made your decision, and now you must climb until you succeed or until you fall. You have already calculated the risks and have already accepted the consequences of falling. Thus, there is no value in second-guessing yourself or ruminating on your dilemma. In fact, you are most likely to succeed at this point if you climb boldly and confidently. Any hesitation will undermine your prospects.

After you make the committing move, you must close the feedback loop. Whether you made the move or fell, you have much to learn. You now have a new entry in your repertoire of life experience. How accurate were your judgments about the probability of success, or the consequences of failure? What was your mental state? How could you have improved? If you succeeded, are you honestly digesting any lessons or is your ego rushing you to overlook them? If you fell, what did you learn? How are you growing?

As you gain proficiency with committing moves, they become habitual. You will regularly encounter new kinds of moves, but internalize the psychological process for meeting them. You build up an experience base with falling, which will help tame your fears about future falls and help you distinguish safe falls from unsafe ones.

Like many things in life, learning to make committing moves is a lifelong journey. I am still learning. Each time I encounter one, I take a long pause, close my eyes, and focus on my breathing. I wait for the shakes to pass. Then I make my decision. Sometimes I succeed, sometimes I fall. Slowly, I am getting better.